GREG BENSON PHOTOGRAPHY

This article was originally posted on philly.com

The most powerful factor shaping the look of Philadelphia neighborhoods isn’t architectural style, and it isn’t money. It’s the city’s street grid. It literally keeps our buildings from stepping out of line.

That orthogonal discipline has given us plenty of fine ensembles, such as the rows of exuberant Victorian houses that make up Spruce Hill and, more recently, the handsome new Transatlantic development at Fifth and Fairmount in Northern Liberties. The grid also does a good job of establishing the ground rules for infill development, ensuring that old and new can exist in harmony.

At the same time, the regimentation of the grid can impose a dreary conformity on the city. There are few opportunities here to create interesting architectural hierarchies, and that leads to long runs of similarly scaled buildings. Unlike Washington or Paris, where intersecting diagonal streets form high-profile nodes, there aren’t many places in Philadelphia where a building can punctuate the street. The Art Museum, sitting atop its hill at the end of the Parkway, is the city’s premier exception.

Architects refer to such show-offs as “object buildings,” to distinguish them from the everyday, background buildings. While object buildings are often civic or cultural destinations, they don’t have to be. They just have to stand out from the crowd.

That’s what makes the diminutive newcomer at 39th and Chestnut such a delightful surprise. It’s an ordinary building, wedged in the middle of the grid, and yet it is an object building all the same, thanks to its assertive attitude and appealing sculptural form.

Designed by Sergio Coscia of Coscia Moos Architecture, the sharply angled, glass-and-metal structure was inserted into the former courtyard of Hamilton Court, an early-20th-century hotel that long ago was converted into student apartments. Just two stories, it was built to house a gym, pool and sun deck for the apartment building. It’s what housing developers call an amenity space.

HALKIN MASON PHOTOGRAPHY

But what an amenity space! A dark aluminum veil, almost bronze in color, rests lightly on a glass box, giving the little building a whiff of mystery. Folded like origami, the veil angles up, before cutting away to reveal two rhomboid-shaped openings. The crease across the center causes the metal scrim to bulge forward, poking its nose over the sidewalk. The scrim extends out just three feet, but that’s far enough for passersby to get a hint of the building as they head up Chestnut Street.

Because the aluminum is perforated, the veil casts dappled shadows across the glass box. The light is always in motion, changing with the sun. Coscia says the openings account for 18 percent of the surface area, a magic number that prevents snow from accumulating on the surface in the winter and the sun from overheating the second-floor gym in the summer. The veil echoes the metal scrim that shields the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington.

An old student apartment building isn’t normally where you expect to find this sort of architectural statement. Most student housing in West Philadelphia is maintained at a level just good enough to escape the notice of the authorities. Despite Hamilton Court’s architectural pedigree, that was the case here until the property was purchased from Michael Karp in 2015 by the Post Brothers, for $40.5 million.

The Post Brothers specialize in buying rundown apartment buildings and bringing them upmarket. This usually involves adding amenities to make the renovated apartments more attractive to tenants. They’ll glam up the lobby, build a pool, install a co-working nook, and pack the ground floor with retail. Lots of developers around Philadelphia are following the same script these days, creating something of an amenities race. That explains why so many new buildings now have their own dog parks and golf-simulation rooms.

THE POST BROTHERS

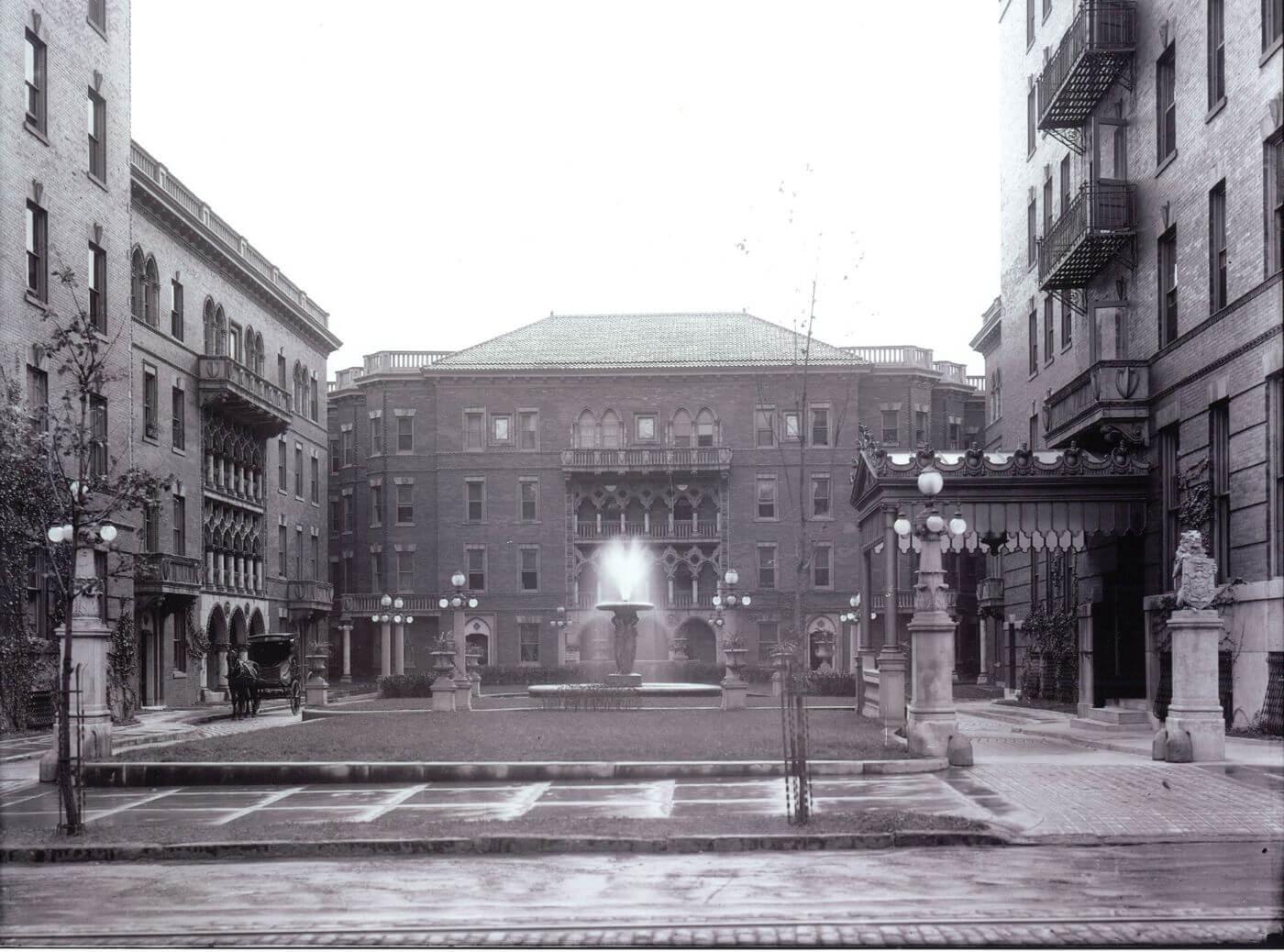

At Hamilton Court, the challenge was figuring out where to put everything. Designed in 1901 by Milligan & Webber, the unusual, Venetian Gothic complex was built as a long-term stay hotel, probably for wealthy Penn students and their parents. Although it once featured a rooftop restaurant, there wasn’t enough space within the building for a modern gym and pool, said Michael Pestronk, Post Brothers CEO.

Hamilton Court did have plenty of room outside, however. The hotel was built in stages by its original developer, William Hamilton, ultimately forming a U-shaped building around a courtyard. Landscaped with a lawn and fountain, the courtyard allowed horse-drawn carriages to pull up to the front door.

By the time the Post Brothers acquired the property, that gracious courtyard had been paved over for parking. A dumpster took the place of the fountain. Worse of all, a crude stockade fence walled off views of the stunning Venetian-style terraces.

Sadly, Coscia’s amenity building also blocks those views. Yet it does so in a way that preserves public access to the courtyard and Hamilton Court’s gorgeous facade. You can walk around the little building, enjoying close-up views of the intricate Venetian loggias and luscious, honey-colored brick. There was enough space left over in the courtyard for benches and cornhole games. The amenity building makes the huge courtyard feel more intimate and usable. It’s an immense improvement over the wooden fence and asphalt paving. Soon there will be two restaurants facing Chestnut Street, a French sandwich shop and Vietnamese street food restaurant.

But the amenity building does change the way we see the two wings of Hamilton Court from Chestnut Street. They now read as separate structures, bookending the dark crystal of the amenity building.

While modern interventions often play off a historic design, borrowing a certain shape or material, Coscia refused to defer to Hamilton Court’s architecture. His building insists on being its own thing. That extreme contrast, Coscia argues, is no different from the relationship between I.M. Pei’s modern glass pyramid and the Louvre in Paris.

Had the architecture been less deft — a stucco box, for instance — that argument would have fallen flat. But this design, which cost a whopping $6 million, is good enough to justify its transgressions. We need to preserve our historic buildings, but we also need to create ambitious modern designs. Every once in a while, it’s a relief to see an object building escape the straitjacket of the Philadelphia grid.